April 17, 2023

IMAGE: The MV Cape Ray enters a port in Gioia Tauro, Italy, on July 7, 2014, in preparation to receive cargo containing specific chemical agents from MV Ark Futura, a Ro-Ro cargo ship. Photo by Mass Communication Specialist Seaman Desmond Parks for the US Navy.

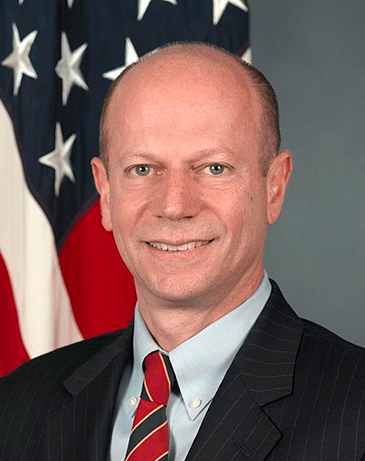

Andy Weber served as the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear, Chemical, and Biological Defense Programs. He describes how multinational cooperation and respectful relationships with counterparts in other countries contributed to the successful elimination of the Syrian stockpile of chemical weapons during the Syrian civil war.

Interviewed by Nick Roth.

ANDY WEBER: The number 1,300 tons, it sounds like it’s an ocean. It’s an impossible amount. How do you deal with that? It becomes thinkable that you can accomplish this, and indeed, it proved itself right.

So my name is Andy Weber. I served in the government of the United States for 30 years, mostly at the Pentagon. And my final job was a presidential appointee. I served as Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear, Chemical, and Biological Defense Programs for 5 1/2 years.

In 1998, I was a mid-level Pentagon official involved in the Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction program, and we were trying to get some bio-defense cooperation started with Russia. A small group of us were invited to the Russian nuclear, chemical, and biological defense training facility at a place called Tambov, Russia. It was an overnight train ride south of Moscow, and our host was a General Viktor Kholstov, who at the time was Commander of the NBC Defense Forces of the Russian Federation.

And it was in December of ’98. Snow was this deep on the ground, and we spent over two days getting demonstrations of some of their equipment and their training, and it was a really remarkable experience for all of the Americans who, you know, were part of this visiting delegation, and I got to know General Kholstov very, very well. I spoke Russian fluently at the time, and we became good colleagues, even friends, I would say, by the end of the visit.

2011, unrest, civil unrest began during the Arab Spring in Syria, and we became, just like we were worried about loose nukes when the Soviet Union collapsed, we became concerned about loose chemicals. We had exquisite intelligence on Syria’s chemical weapons stockpile, and we were concerned that Syria might use these 1,300 tons of chemical weapons against its neighbors, Israel, Jordan, Turkey, or possibly against its own population, or that al-Qaeda affiliates, like al-Nusra Front, would gain possession of these chemical weapons, and use them in terrorist attacks.

So it became a very, very high priority for me and for our team at the Pentagon to figure out what we should do to be prepared to deal with this. And we started actually in 2011, and then in 2012, set out to build a technology called the Field Deployable Hydrolysis System. It was two shipping containers that could neutralize Syria’s chemical weapons, like sarin especially, and VX, and other chemical weapons they had, and we didn’t know if they would ever be used, where they would be used, inside Syria, although during a civil war, it didn’t seem likely, perhaps in Jordan, or Albania. Eventually, it was decided to do it on a ship sailing around the Mediterranean.

In March of 2012, we had reporting about a very small scale chemical weapons use by the Syrian regime against its own people. It didn’t make public news, but we had a series of meetings in the Pentagon, and a few weeks later, I was in The Hague in the Netherlands, home of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons.

And I decided to invite my counterpart, General Kholstov, to lunch, and we had lunch at an Italian restaurant in The Hague. The purpose for us being in the Netherlands was to update the OPCW on progress in destroying our respective chemical weapons arsenals. But I took advantage of this lunch to talk to him about Syria. And after reminiscing about some of our shared experiences together, the visits to Missouri, to Tambov, Russia, I briefed him on the technology that the Pentagon was building to destroy Syria’s chemical weapons.

It was just me at this meeting. I decided not to take staff with me, in part because I still spoke fluent Russian, and didn’t wanna have to bring non-Russian speakers to the meeting, and have the awkwardness of working through interpreters.

So at this lunch in an Italian restaurant in The Hague with General Kholstov, Colonel Rodyushkina, and one other Russian official. I described the concept for moving Syria’s stockpile safely out of Syria to the port, and then loading it onto ships, perhaps moving it to Jordan, or Albania, or some other third country, where it could be safely destroyed in an environmentally harmless manner.

And the whole concept of moving chemical weapons, it wasn’t even certain if that was legal, if countries could do that, but if the purpose was to destroy the stockpile, our lawyers determined that yes, we could do that. And the logistical challenge of doing this during a civil war was enormous.

But because of our relationship, because I had known this gentleman for well over a decade, and the respect that we had built, we had a very good discussion.

He started out as very skeptical. They had a lot of hard questions, and by the end of the lunch, I think we had a common understanding that it was actually possible to do this. I never reported on that lunch. I didn’t write a cable back to Washington. I was so busy at the time. But to me, it was sort of a symbol of how we could work together, Russia and the United States.

Fast-forward to August of 2013, this is about six months, almost six months after the lunch in The Hague with my Russian counterpart, General Kholstov. The Assad regime launches a brutal chemical weapons attack with sarin gas, killing many, many, many men, women, and children. It was just a horrible, horrible use of chemical weapons, which are banned, and the United States prepared with its allies to launch a military strike in response to that.

Of course, bombing chemical weapons is very problematic, ’cause it can spread contamination, which can last for many, many, many, many years.

And under the threat of military force, President Obama and President Putin had a discussion that maybe there was another way, if Russia could pressure Syria to join the Chemical Weapons Convention, and work to destroy them peacefully. And indeed, Secretary Lavrov, or Foreign Minister Lavrov, and Secretary Kerry met in Geneva in September of 2013, and signed an agreement to work together to destroy Syria’s chemical weapons.

And it was an incredible example of international cooperation.

We had over 30 countries contributed either finances, financing, or technical capability. The UN was very involved in this. We had a Security Council resolution. Imagine, we had a Danish ship in the Syrian port being protected by Russian and Chinese naval vessels.

It was just an incredible example of multinational cooperation to solve a problem. But it looked like it was a spontaneous proposal. The negotiation was very fast and very successful. The timeline for executing the project was extremely ambitious, but we met it, we did it.

People thought it was not possible, and I think the reason we were successful is all that planning, several years of planning that went into it, and working with our Russian counterparts, and having those relationships that had been built up during the US-Russia Nunn-Lugar years.

The United States had exquisite intelligence on the Syrian chemical weapons program through a high-level penetration of that program, who worked for the CIA for over 14 years. So we knew in great detail granularity everything about the chemical weapons stockpile.

But the number 1,300 tons, it sounds like it’s an ocean. It’s an impossible amount. How do you deal with that?

Well, I decided, because it was at eight, or 10, or 12 different sites at a given time, that I would task our Defense Threat Reduction Agency with calculating how many truckloads would that be? And they did the math, and came back with the answer of about 200 truckloads. And all of a sudden, if you’re thinking about, you know, maybe different sites becoming accessible over time, 10 truckloads at a time, or 20, it becomes thinkable that you can accomplish this, and indeed, it proved itself right.

It was about 200 truckloads of chemical weapons that were moved by the Syrians to the port at Lattakia that were then loaded onto ships for transport and transloading onto the US vessel that destroyed them.

So it was reducing the problem to a number that people could relate to, could understand, not just a big number of, you know, 1,300 tons.

It’s hard. When relationships sour, it’s hard to keep these programs going. One example is 2014, when we actually moved the Syrian chemical weapons stockpile onto ships, and then eventually onto a US ship for destruction, that was the same time that Russia invaded Crimea, and our relations had never been worse. But we managed right up to the end of that operation to continue to keep communications open to work on finishing this project.

Sometimes, whether it’s Gaddafi in Libya, or Assad in Syria, it’s unsavory characters, who have these horrific weapons. And you have to work with them sometimes, and it’s hard, and it’s challenging, and you have to keep your eyes open. You need to make sure you’re not indirectly helping them in another area. But that’s where good oversight comes in, and you have to think about the objective of all these programs. The objective is to save lives, to prevent mass casualties in any country, anywhere in the world. These are global programs that improve global security.

Well, I think another important aspect of this story, this accomplishment, is that a lot of the people who were involved in the government at the time had experience in the Nunn-Lugar program working with Russia, Kazakhstan, Belarus, Ukraine. And so, the approach was something we had all lived and understood.

You had people like Ash Carter, Elizabeth Sherwood-Randall, Laura Holgate, myself, who had that experience to draw on. And so, we knew it was possible. We knew it was doable, because we had done similar work in the past in very difficult circumstances. And it was that confidence that we could do this that I think made us ambitious.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Stanley Center for Peace and Security or any other agency, institution, or partner.

Mr. Weber has dedicated his professional life to countering nuclear, chemical, and biological threats and to strengthening global health security.

Mr. Weber’s thirty years of US government service included five-and-a-half years as President Obama’s Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear, Chemical and Biological Defense Programs. He was a driving force behind Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction efforts to remove weapons-grade uranium from Kazakhstan and Georgia and nuclear-capable MiG-29 aircraft from Moldova, to reduce biological weapons threats, and to destroy Libyan and Syrian chemical weapons stockpiles. In addition, he coordinated US leadership of the international Ebola response for the Department of State.

Prior to joining the Pentagon as Advisor for Threat Reduction Policy in December 1996, Mr. Weber was posted abroad as a US Foreign Service Officer in Saudi Arabia, Germany, Kazakhstan, and Hong Kong.

Mr. Weber is an independent consultant and a Strategic Advisor for IP3 International and Ginkgo BioWorks. He serves on the James Martin Center for Non-proliferation Studies International Advisory Council and is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations. He taught a course on Force and Diplomacy at the Georgetown University Graduate School of Foreign Service for seven years, and was a Senior Fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Mr. Weber graduated from Cornell University and holds a Master of Science in Foreign Service (MSFS) degree from Georgetown University.

The Stories