Working relationships with a nuclear adversary involve years of trust building. They are constantly tested by events. And when the relationship is betrayed, it can raise catastrophic risks. Recreating such a relationship seems impossible without looking back to see how it survived previous crises.

After NATO intervened in Kosovo with air strikes in March 1999, Russia cut off all contact and relations with the United States. The chilling effect reached programs of mutual interest, like the Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) program to reduce threats from weapons of mass destruction in the former Soviet Union.

I had been part of the CTR program for years at that point. General Major Vladimir Frolov of the 12th Main Directorate (GUMO)[1]—which was responsible for security and management of Russia’s nuclear weapons—and I had established a regular phone call that we conducted every two weeks. The calls were pretty one sided. Our side would share as much information as we could on the status of our contracts and work being performed, while the 12th GUMO limited its responses to acknowledging dates and schedules for upcoming technical meetings.

Soon after NATO intervened in Kosovo, I informed Frolov that CTR work would continue unabated. Since these were regular calls focused on implementation of this work that the 12th GUMO wanted to continue, our lines of communication remained open. He told me that all senior level exchanges would be canceled for the next three months in response to NATO actions. Our technical team efforts would also be put on hold for one month, after which we could resume our visits to oversee the work and conduct technical talks on future requirements. I passed this information to our policy leadership in the Pentagon and at the National Security Council to let them know that the disruption of the program would not be permanent and that the Russians planned to resume the relationship after a short break.

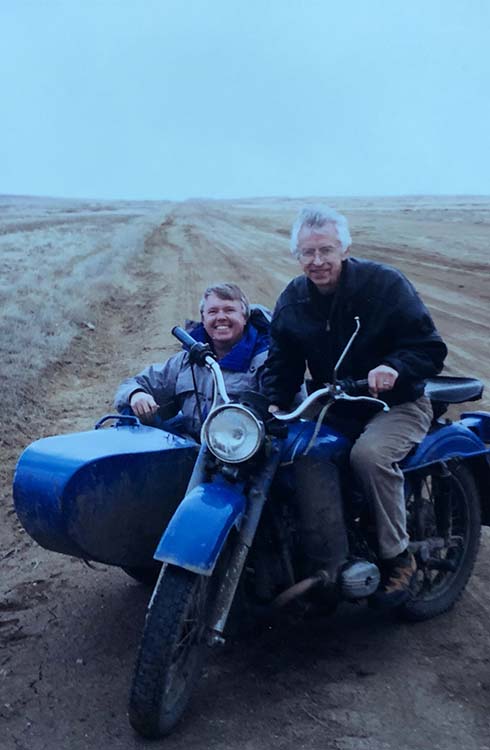

Bill Moon

Bill MoonWilliam Moon (L) and General Major Vladimir Frolov (R) of the 12th Main Directorate (GUMO).

The relationship we had established with our Russia counterparts that helped us weather this crisis did not happen overnight. In more than four years that preceded the crisis, I led over seven technical team trips, and CTR project teams made a half-dozen trips, to meet with our Russian colleagues. That was in addition to the teleconferences that took place every two weeks. Our commitment was also expressed through a budget that went from $3 million for the first project to over $50 million annually for the work supporting the Russian Ministry of Defense (MOD). And we were just getting started—we jointly developed plans for extensive work to secure the entire Russian warhead inventory

Looking back, it’s hard to imagine returning to that kind of relationship anytime soon, given the war that Russia is waging on Ukraine. Not long ago, the two largest nuclear superpowers were able to work together to secure nuclear warheads—their most valued political and military assets. It’s important to remember what made that work.

My adventure started with the establishment of the CTR program in 1992. I supported nuclear warhead security and the elimination of missiles, silos, and submarines. I worked with the Russians to reduce the nuclear stockpile and eliminate excess sites and facilities supporting nuclear weapons.

Under CTR, we had a close, professional relationship with the MOD and one of its most elite and secretive organizations in charge of its nuclear warheads, the GUMO. We worked closely together with Russia for 18 years. We even worked together in developing and fostering mutual relationships with Belarus, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan.

Many stories and academic studies examine high level negotiations on arms control. Those stories are exciting and illuminating; they provide important strategic insights. You don’t hear as many stories from a “mid-level bureaucrat”[2] like me, who managed programs and initiatives launched by the agreements. If you really want to understand how to promote nuclear risk reduction, you need to understand how people, teams, organizations, and states can work together.

William F. Burns—US special envoy on the safety, security, and dismantlement of nuclear weapons—led negotiations in fall 1992 that resulted in Belarus agreeing to give up its nuclear weapons and accede to the Non-Proliferation Treaty as a nonnuclear state. Belarus was the first of the former Soviet states to ratify the arms control treaties and accept US CTR assistance. Three Strategic Rocket Force bases at Postavy, Lida, and Mozyr were on Belarussian territory housing 81 nuclear-armed SS-25 mobile ICBMs.

Defense Threat Reduction Agency

Defense Threat Reduction Agency2CYYW8Y Workers stand inside of a reactor at Atucha II nuclear power plant in Zarate, some 100 km (62 miles) north of Buenos Aires, September 28, 2011. Argentina began the final tasks for its new nuclear power plant which will be operational in 2012, as part of an official plan that seeks to reactivate nuclear activity which had been stagnant for over a decade. The Atucha II plant will operate with natural uranium and will provide 692 megawatts to the national power network. REUTERS/Enrique Marcarian (ARGENTINA – Tags: POLITICS ENERGY SCIENCE TECHNOLOGY)

With agreements in place, it was urgent that the work to eliminate the bases and remove the weapons be implemented as quickly as possible. As a project manager at the Defense Nuclear Agency (DNA),[3] I joined Paul Boren’s team to work this mission. I had been to the Soviet Union once, in 1990, and Russia in 1992, but Belarus was a new, unknown entity. We arranged our first trip to Belarus in September 1993 and another at the end of November. I supported four more trips through April 1995.

Endnotes

[1] Glavnoye Upravleniye Ministerstvo Oborony.

[2] That’s how historian Joseph “Pat” Harahan described me in his book on the CTR program, With Courage and Persistence.

[3] DNA became the Defense Special Weapons Agency (DSWA) in 1996, then the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) in 1998.